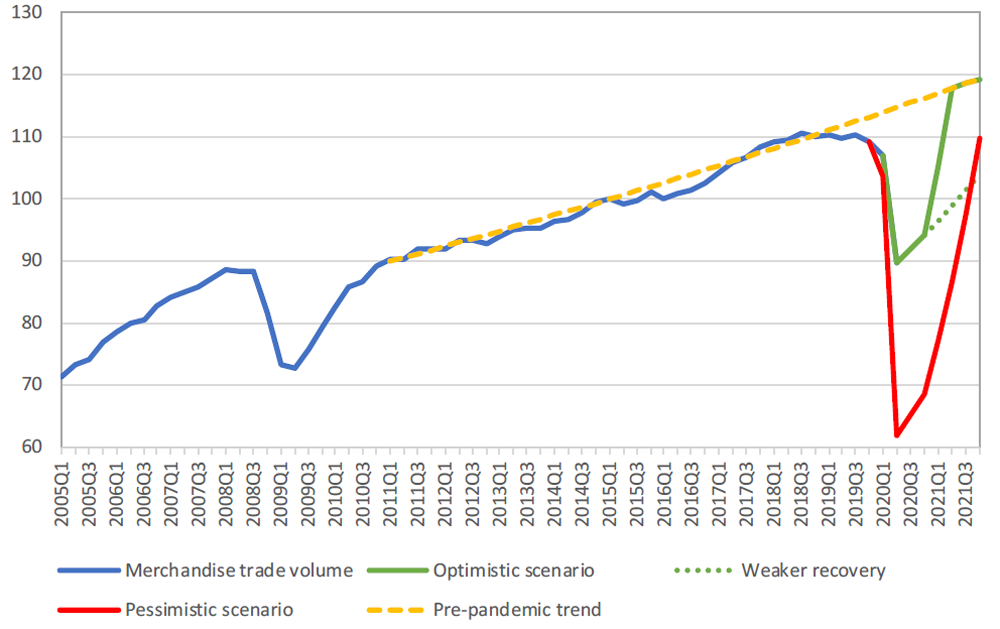

Global trade is slowing at an unprecedented rate, as illustrated in the chart below. This trend had started long before COVID-19 had made its inroads. This may appear surprising as firms are more networked and increasingly rely on global supply chains.

In recent times, the efforts for time-bound compact trade deals have received great attention. Under the HS system of tariff classification, there are around 5,200 tariff lines at the six digit level or roughly 11, 000 products at the eight digit level. In a typical free trade agreement (FTA) negotiation, most of the tariff lines with the exception of certain sensitive or excluded lines will be amenable for tariff reduction or elimination. In other words, FTA negotiations often include a wide basket of products and consequently a broader range of tariff, non-tariff and other regulatory issues.

Limited scope compact trade deals appear as an anathema to the concept of broad trade and economic integration. There is a danger that they could serve as minor preferential schemes which are discouraged under multilateral trade rules. The WTO rules emphasize on trade agreements encompassing ‘substantially all trade’, which implies that FTAs cannot be selective in their scope and coverage. However, as the past WTO interpretative practice indicates, the accordion of ‘substantially all trade’ tends to stretch and squeeze to confer greater flexibility to FTA parties. This concept is rooted in pragmatism as few countries have the appetite to embrace unfettered free trade.

World merchandise trade volume, 2005‑2021Q4

(Index, 2015=100)

Source: WTO/UNCTAD (2020)

There is a real need to move the juggernaut of trade negotiations from its deep freeze. What can be the way forward?

Rationale for compact trade deals

Until recently, the whole world was preoccupied with the mega-regional trade agreements. Mega-regionals seek to deepen trade liberalization and address, in addition to traditional trade issues, new age topics such as e-commerce, data privacy, disciplines on state-owned enterprises, investment protection, currency practices, competition and social clauses. The Trans-Pacific partnership (TPP) agreement, famously touted as the ‘trade agreement for the twenty-first century,‘ and a ‘pivot to Asia’ was the trend-setter in this regard. The TPP was, however, thrown into disarray with the United States withdrawing from it in 2017. The much acclaimed Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) was stalled even before making any reasonable progress. The Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) negotiations despite being so close to closure may be awaiting a similar fate with several negotiating parties getting into political spats. The only major trade agreement to have emerged successfully from the welter of failed trade deals in recent times is the Canada – European Union Trade Agreement (CETA). In short, megaregional trade agreements have not yet been able to deliver on their promises.

The list of failed trade negotiations and aborted trade agreements is vast and numerous. The most famous among all is the International Trade Negotiation (ITO) initiated as part of the Havana Charter negotiations. Five decades later, the Doha Round was launched with fanfare in the aftermath of 9/11 attack on the World Trade Center. The Doha Round promised to augur global cooperation on several fronts, but petered out with a rather insignificant agreement on trade facilitation slightly over a decade later. In 2003 President Bush declared a promising FTA titled the ‘Free Trade Area of the Americas’ which received very little traction. There are several other failed trade negotiations in the last couple of decades.

The cost of failed negotiations is not often estimated and well analyzed. Travel, logistics and administrative cost of conducting decade-long trade negotiations are not insignificant. The most serious concern, however, is the opportunity cost of delayed and failed negotiations. When strategic global economic co-operation can accentuate growth, lessen poverty, and strengthen economic stability through access to global markets, it is important to think beyond the standard templates for trade negotiations.

‘Transactional FTAs’ filling the gap

There is a recent focus on leveraging trade negotiations to achieve immediate and tangible trade outcomes. The thrust of such negotiations is not to negotiate endlessly but to reap the harvest of initial understanding on certain areas or sectors of mutual interest and move forward. It is indeed possible to structure phased trade agreements by locking in the progress and embarking on tougher and more complex areas later in the negotiations. From a political economy point of view, such agreements will look good to domestic constituencies and need not attract the same type of adverse publicity which outsized mega-regional and multilateral trade negotiations often elicit.

Transactional FTAs can be different from regular FTAs. Such agreements can dispense with the need for complicated rules of origin negotiations, especially if they are bilateral in nature. Tariff reductions are unlikely to take place if free-riding is a genuine possibility, however staged market access through effective administrative and import licensing means can be a possibility. While transactional FTAs are bilateral or trilateral in scope, they cannot afford to discriminate against non-parties the same way most FTAs or economic integration agreements do. In other words, tariff preferences have to be extended on an MFN basis across the entire WTO Membership in consonance with the GATT principles. By their nature, transactional FTAs can only take place where the parties have a natural and overwhelming competitive advantage in certain products.

Transactional FTAs can be particularly useful in addressing traditional behind-the-border issues such as regulatory and administrative measures. Securing low or even zero bound rates of duty in WTO or FTA negotiations is meaningless, if there are no domestic mechanisms for evaluating and accepting product certifications, process standards or matters of regulatory coherence. To give an example, the WTO SPS Agreement states that the SPS measures have to be adapted to regional characteristics. In India’s case, the 1898 Livestock Importation Act and its rules did not explicitly provide for recognizing safe imports in livestock based on regional characteristics until an enabling notification was made in 2016. Regulatory co-operation is very poorly addressed in most trade agreements. Transactional FTAs providing for regulatory cooperation need not be exclusionary; on the other hand, such agreements can provide a framework for others to join or initiate a similar effort.

Traditional FTAs are signed for perpetuity, although technically they can be terminated after giving notice. Transactional FTAs, on the other hand, given their less formal character, provide for sunset clauses which provide ample opportunities for a party to get out of a bad deal. The United States- Mexico- Canada (USMCA) which replaced NAFTA provides a review after ten years. USMCA fits the description of a highly comprehensive transactional FTA. Transactional FTAs can become part of a smart trade policy if approached and designed with care.

_____________________________

To make sure you do not miss out on regular updates from the Kluwer Regulating for Globalization Blog, please subscribe here.

Excellent approach if you want to increase corruption and decrease public participation in the decision-making.

Global trade has flatlined in the wake of protectionism and trade wars from the USA. No surprise there. But RCEP, CPTPP and AfCFTA show multilateral trade liberalisation is still doing well.